ZeroesandOnesgoOlympic

The first International Olympiad in Informatics took place in Pravetz, Bulgaria, from May 17-19, 1989, marking a significant step in the integration of computers into everyday life. By the 1990s, digital machines became essential in education and recreational use. A new global competitive platform demonstrated that countries can share similar approaches to technological challenges even despite their irreconcilable ideological differences.

Prominent figures, like Bulgarian computer scientist Blagovest Sendov, spearheaded efforts to integrate computer education internationally, drawing on regional traditions of academic competitions. This initiative aligned with the broader trend of computerization that accelerated with the advent of affordable home computers in the 1980s. As the demand for computer specialists grew, schools worldwide incorporated computer science or informatics into their curricula.

We invite you to explore the journey of how computers became a global phenomenon integrated into the educational system and programming transformed into a competitive discipline.

Camping near the artificial lake in Pravetz, Bulgaria, 1980s. Featured in a tourist leaflet. Source

The first international contest in competitive programming was held in May 1989 in Pravetz, Bulgaria. Since then, the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) has become an annual tournament and the second largest science olympiad after the one in mathematics. In 2023, the IOI competition in Hungary hosted participants from 87 countries.

But in the late 1980s, the event in Pravetz also signified the recognition of computer literacy as an essential part of secondary school education.

| Country | Delegation | Awards | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | 0 | G | S | B | Medals | |

| Bulgaria | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| China | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Cuba | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Czechoslovakia | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| East Germany | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Germany | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Greece | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hungary | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Poland | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Soviet Union | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Vietnam | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Yugoslavia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zimbabwe | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The medal table of the first international computer science school students contest.

Most of the 13 delegations taking part in the first Olympiad in Informatics represented the Eastern bloc, though not all of their countries were deeply integrated with the USSR. However, there were also competitors from Yugoslavia and Zimbabwe—active participants of the Non-Aligned Movement—as well as from NATO member states: West Germany and Greece.

Floppy disk ES 5274 SS/SD 8”. Bulgarian floppy discs produced by IZOT dominated the large Soviet market. (Source: IT Museum DataArt)

In the 1980s, Bulgaria was among the global leaders in computer production. The country held nearly half of the electronic exports within the Eastern Bloc, with 10% of its industrial workforce employed in computer manufacturing. Bulgaria supplied computers for the Soviet space program and nuclear research in India while also competing in the US floppy-disc market through British shell firms.

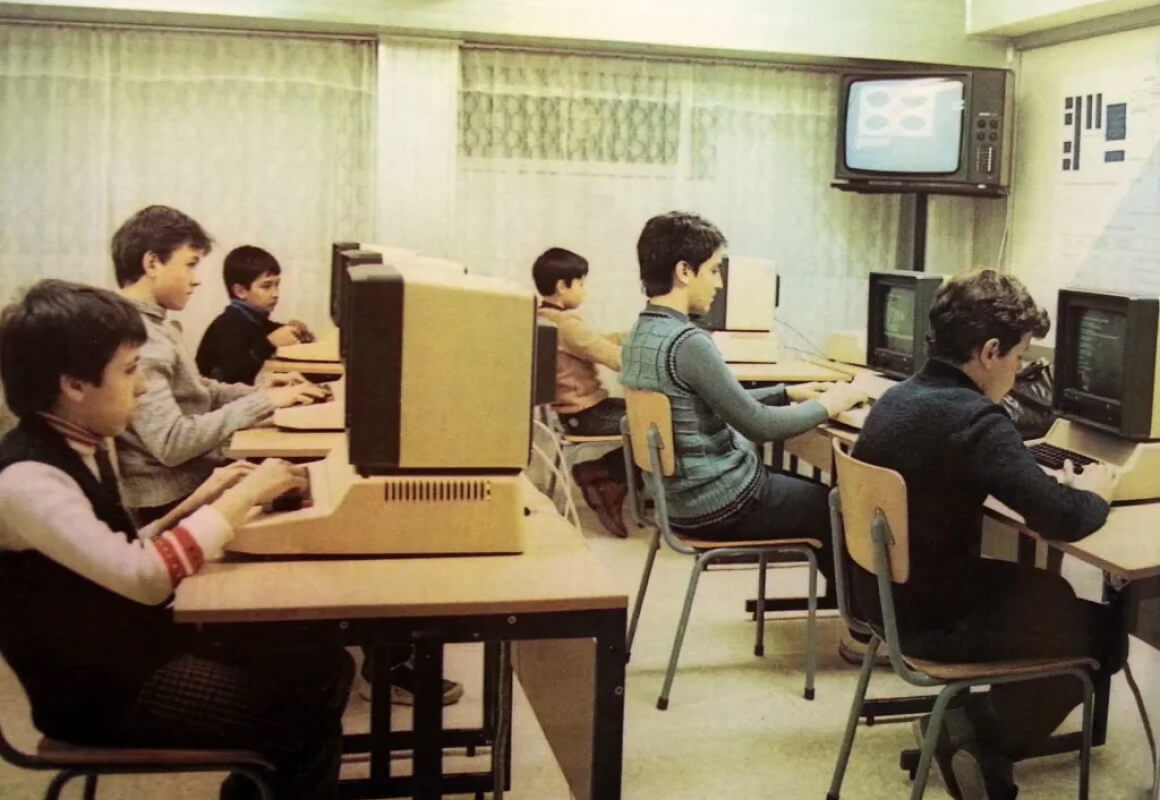

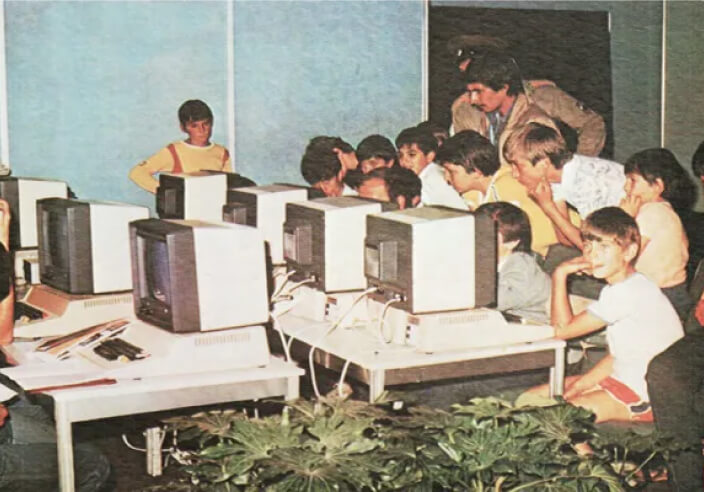

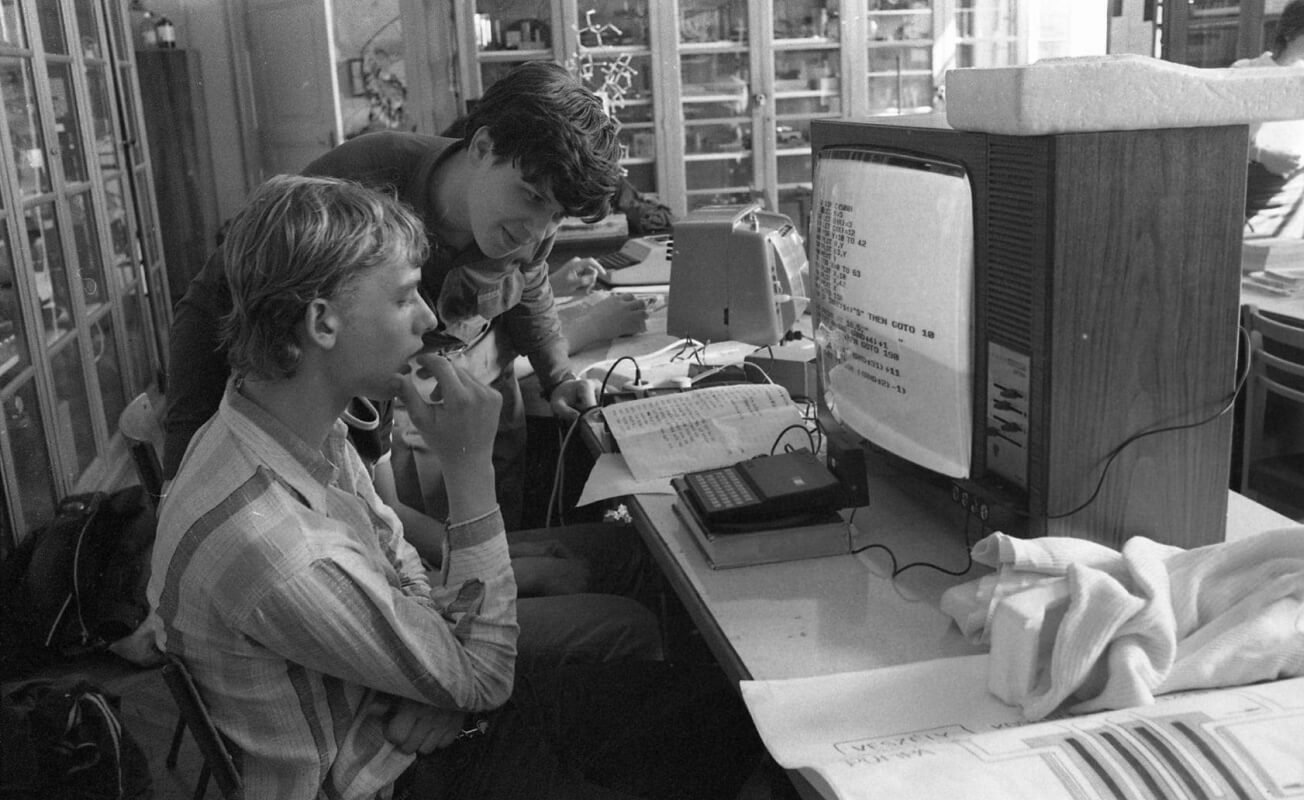

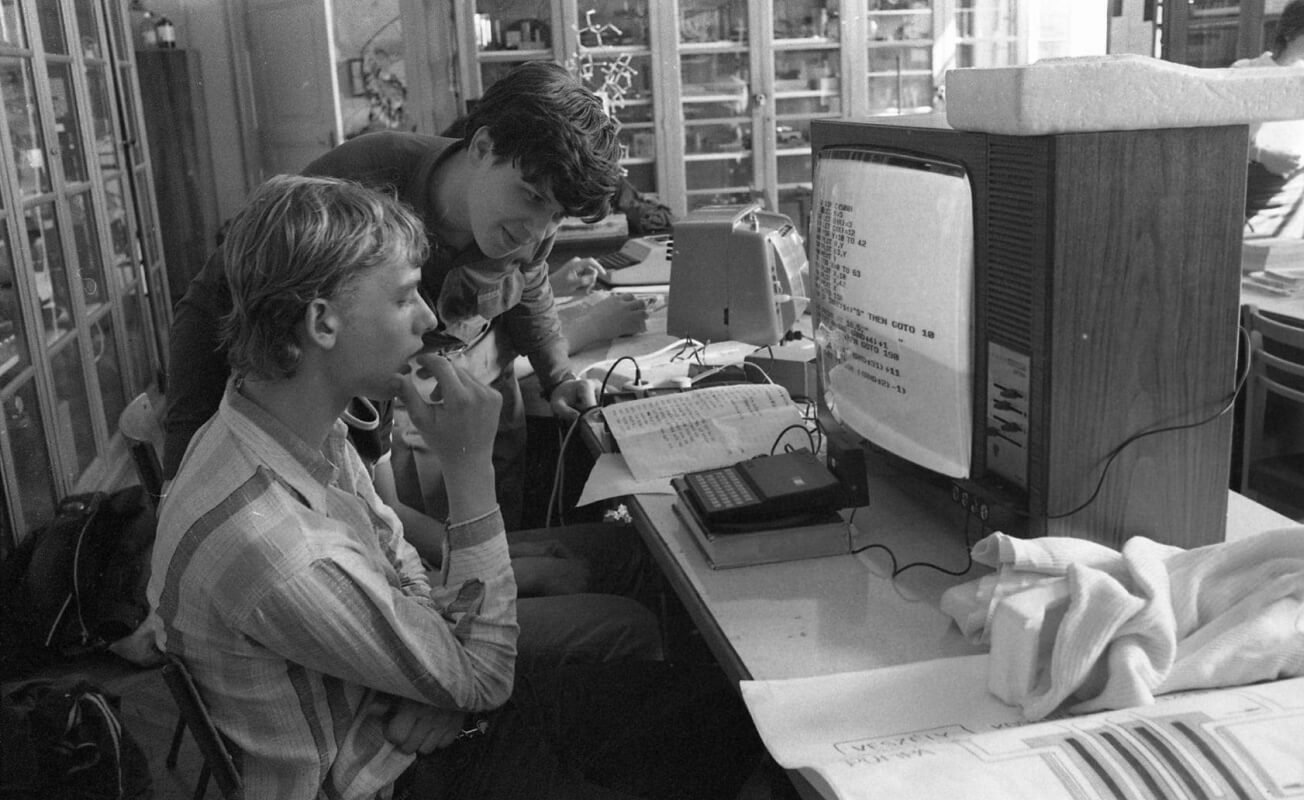

Although personal computers were scarcely available to private consumers in Bulgaria and other socialist countries, young people became acquainted with them through schools and hobby centres.

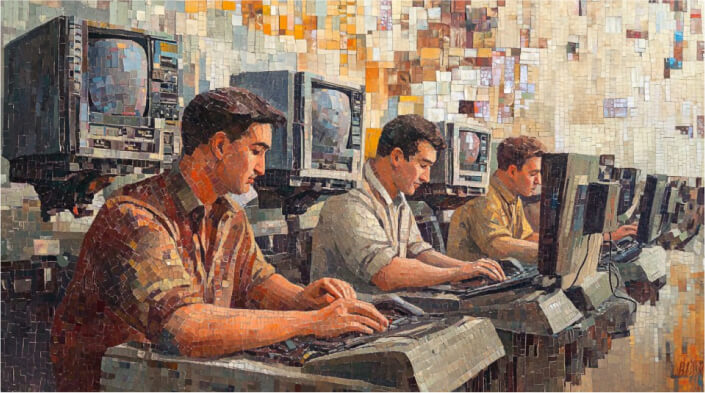

In 1983, one of the schools in Sofia received its first computer room classroom with eighteen Bulgarian personal computers, and informatics was introduced to the curriculum. Within a year, Bulgarian schools received over 300 PCs, and this number kept growing.

By 1987, the Bulgarian Communist Youth Union operated a network of 530 computer clubs, including branches in Addis Ababa, Hanoi, Havana, Kharkiv, Kyiv, Moscow, Leningrad, and Pyongyang.

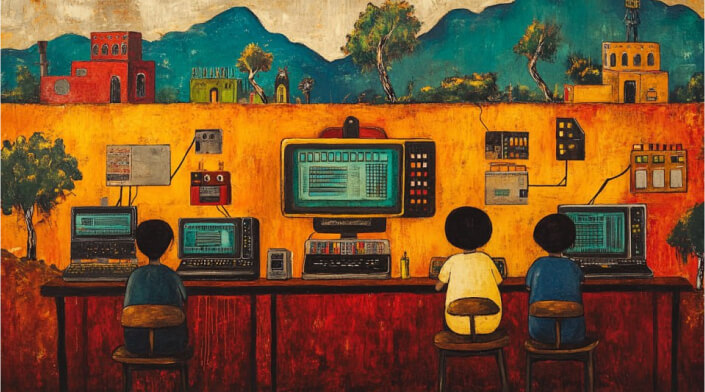

Informatics lesson in a Bulgarian school. Mid-1980s.

In 1984, the new Bulgarian magazine Computer for You, described a computer club at the Sunny Beach resort. Kids from Bulgaria and East Germany got together at the coast of the Black Sea to share their passion for programming.

According to the 1980s Bulgarian media, the mass adoption of computers was regarded as an essential component of the overall society and workforce development. By the end of the decade, in the context of promoting personal initiative, the first semi-private computer firms appeared not only in Sofia but also in Plovdiv, Varna, and Burgas.

Since 1985, various cities in Bulgaria have hosted a biannual international conference, "Children in the Information Age," dedicated specifically to the adoption of modern technology in secondary school education. The promotion of this conference was strongly associated with the outstanding mathematician Blagovest Sendov, who was the President of the National Academy of Sciences, a delegate at the International Federation for Information Processing, and a future diplomat and politician.

In 1989, the conference was held in the city of Pravetz, famous for its contribution in computer design and manufacturing. The first International Olympiad in Informatics was organised as a part of this event.

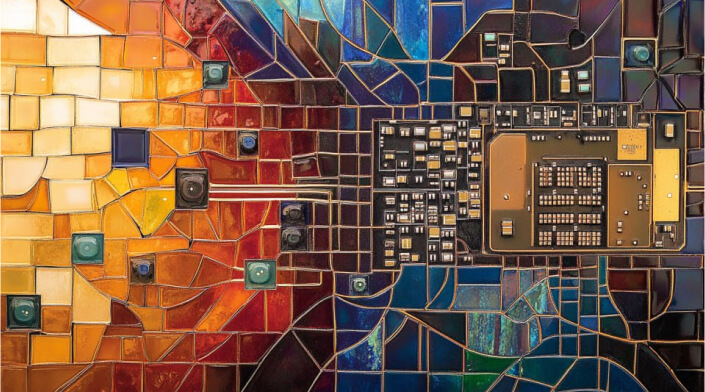

The phenomenon of mass computerization is fundamentally rooted in the availability of desktop computers, which in turn depended on the advent of microprocessors. The first commercially available microprocessor — Intel's i4004— was introduced in 1971.

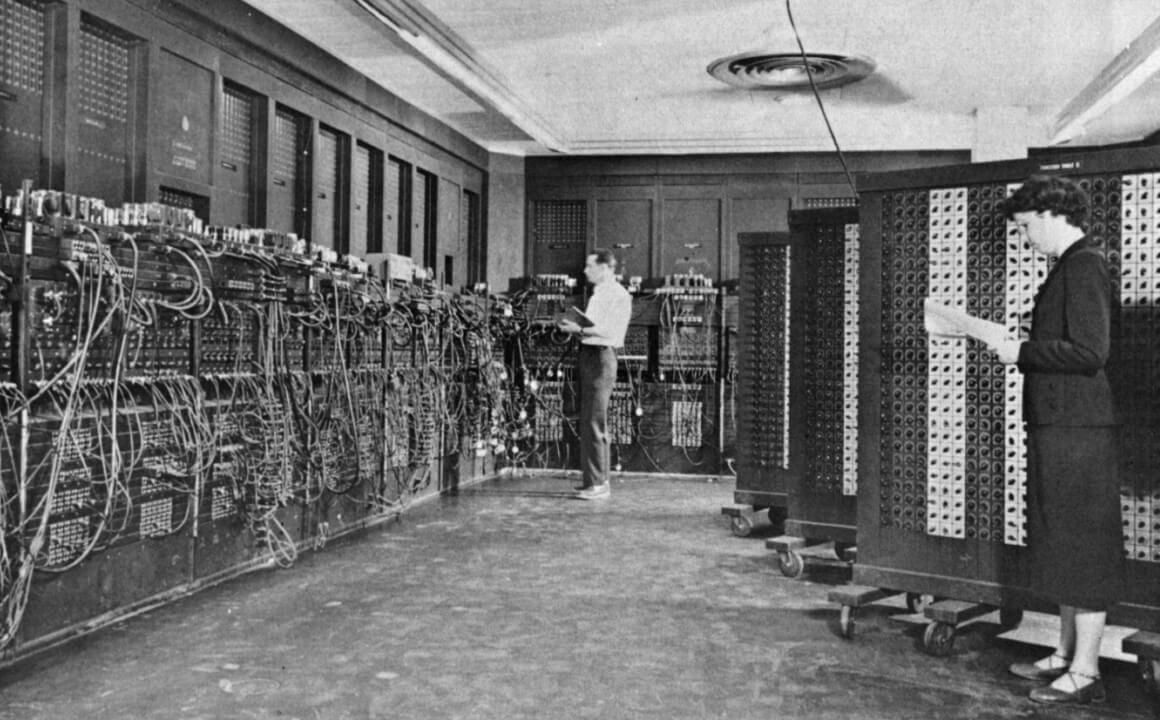

This groundbreaking integrated circuit, containing approximately 2,300 transistors on a single tiny chip, offered processing capabilities previously reserved for large computers. Notably, the i4004 outperformed the pioneering ENIAC from the 1940s by sixfold, achieving 60,000 operations per second compared to ENIAC’s 5,000.

ENIAC in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Glen Beck (background) and Betty Snyder (foreground) program the ENIAC in building 328 at the Ballistic Research Laboratory, 1947. Photo from the U.S. Army photos. Source

This groundbreaking integrated circuit, containing approximately 2,300 transistors on a single tiny chip, offered processing capabilities previously reserved for large computers. Notably, the i4004 outperformed the pioneering ENIAC from the 1940s by sixfold, achieving 60,000 operations per second compared to ENIAC’s 5,000.

Intel introduced its first 8-bit microprocessor in 1972, and two years later released an improved version—the Intel 8080—which became a key component in many microcomputers. Throughout the 1970s, nearly 50 different microprocessors were developed by American and Japanese technological corporations, including Motorola, NEC, Zilog, and Toshiba.

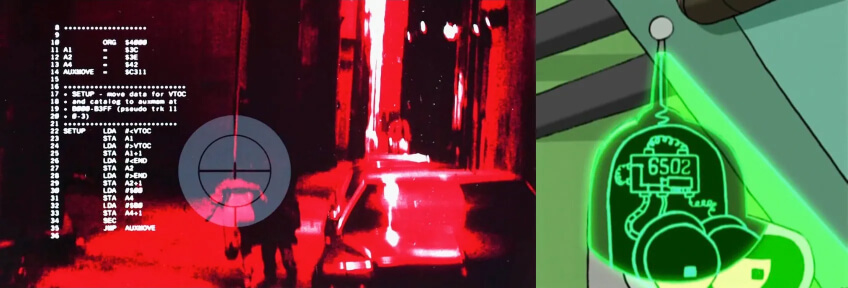

The 8-bit MOS Technology 6502 introduced in 1975 was six times cheaper than Intel 8080 or Motorola’s 6502. Together with Zilog Z80 from 1976, 6502 influenced the home computer revolution of the early 1980s. (See the 6502 microprocessor represented in Terminator and Futurama)

The introduction of the first microprocessors caught the attention of Soviet developers, who acquired information about its development through foreign technical journals and intelligence reports. Despite this, the USSR industry leaders initially overlooked their potential for miniaturisation.

Even in the West during the early 1970s, microcomputers were largely seen as niche devices for hobbyists and engineers. The planned economy further obscured the potential of personal computers. In the Soviet Union, all electronic machines were viewed more as industrial tools or scientific instruments than consumer products for individual households up to the mid-1980s.

Still, research centres and factories all over the Eastern bloc worked on their microprocessors, mostly cloning American examples.

After WWII, the contradictions between the former allies became irreconcilable. The tension surrounding the reconstruction of Europe and the battle for spheres of political influence worldwide led to the formation of two main blocs, led by the USSR and the USA, each with its own military, diplomatic, and economic foundations.

The second half of the 20th century entered history as the Cold War, a period defined by the absence of large-scale military conflicts directly involving the major antagonists. However, it witnessed phases of escalation and demanded continuous efforts in the struggle for technological and ideological superiority.

An East German police officer patrols the Berlin Wall in November 1961. The wall, separating the socialist German Democratic Republic and West Berlin (formerly controlled by American and British forces), became one of the Cold War's iconic symbols. Source

The prolonged confrontation between the Eastern and Western blocs shaped global civilization for decades. The arms race spurred technological and economic advancements but drained resources and intensified fears about the future.

From the outset, electronic computing machines played a pivotal role in this global competition. Integrated into nuclear and missile programs, air defence, intelligence, and communication systems, computers were central to the superpowers' strategies.

The rapid industrial development, followed by the two World Wars and culminating in the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, profoundly shaped expectations for technology and the future. In the second half of the XX century, perceptions took on a dualistic nature, often described as both techno-optimistic and techno-pessimistic.

On one hand, new technologies promised prosperity and inspired hope; on the other hand, they instilled fear, fueled myths and misunderstandings, and spread widespread anxiety. Technology's influence on popular culture occurred in distinct stages, closely tied to the scientific fields that captured the media's attention at any given time.

Group Captain Lionel Mandrake receives orders to put the base on alert. A frame from the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Nuclear or Atomic

One of the most powerful symbols of Cold War tensions was nuclear technology, which dominated the imaginations of many and found its way into various cultural expressions.

Nuclear anxiety became a central theme in sci-fi, exploring both the terror and fascination with atomic energy. These themes weren’t limited to weapons but extended to the potential for energy solutions and the unpredictable outcomes of radiation. Mutants, nuclear holocausts, and post-apocalyptic worlds became fixtures in sci-fi, offering chilling glimpses of possible futures shaped by the power of the atom.

Space Travels

The Cold War ignited interest in space exploration, fueling dreams of interstellar travel and extraterrestrial life. Sci-fi narratives depicted space not just as a battleground between superpowers but as a symbol of human ambition and curiosity.

The “Star Trek” TV series, first aired on September 8, 1966, resonated with viewers at a time when space exploration was still a new and exciting frontier. Although home video technology didn’t exist to spread its popularity, the series was adapted into photo novels by James Blish, expanding its reach. The show’s influence persists today, reflecting humanity's hope for peace and exploration beyond Earth's borders.

Genetic Engineering and Mutation

During the Cold War, advancements in biology, particularly in genetic engineering and mutations, ignited the imaginations of science fiction writers. Themes of eugenics, altered human biology, and unintended consequences became fertile ground for storytelling, inspired by earlier works of H.P. Lovecraft and H.G. Wells.

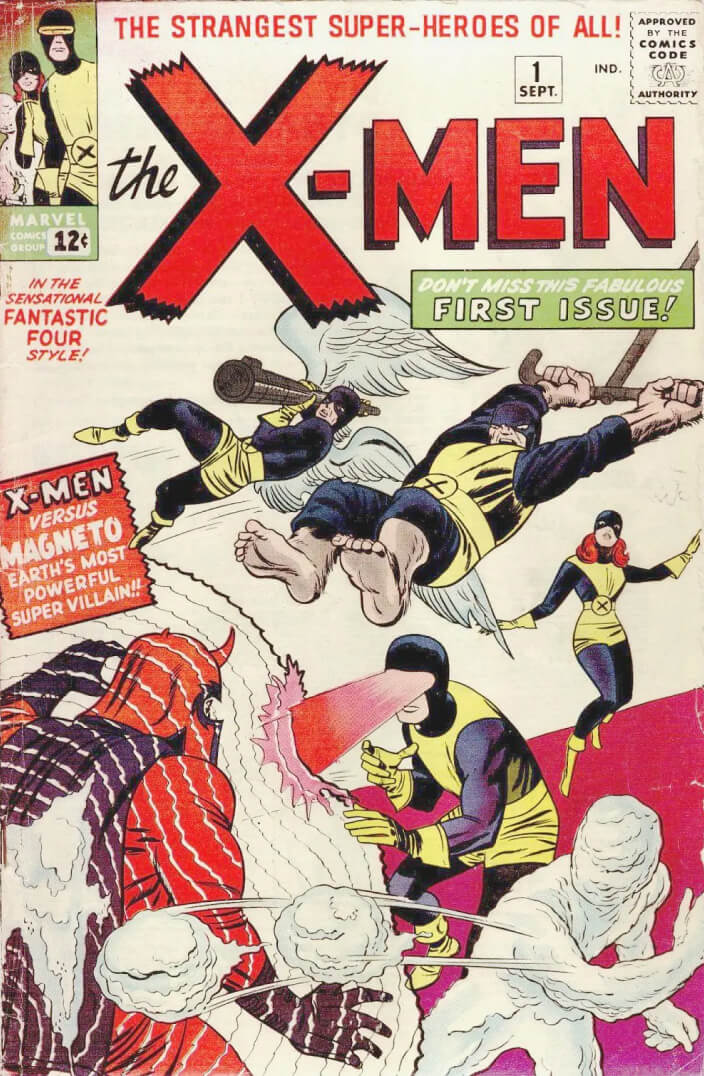

One of the most enduring examples is the X-Men from the Marvel Universe, portraying the ethical dilemmas and potential dangers of altering human biology.

This tension between advancing human capabilities and the fear of losing control over science mirrored broader Cold War anxieties—particularly concerns over nuclear technology, arms races, and the unpredictable consequences of scientific progress.

Cybernetics and Robotics

Since the early 1900s, robots in literature have symbolised humanity’s fears of being replaced by machines or losing our identity to them. As automation advanced, the anxiety deepened. The use of words like “think,” “choose,” and “decide” to describe computers and robots made them seem more lifelike, yet still alien and even more unsettling.

Isaac Asimov, one of the most well-known authors in the field, began to explore robotic ethics in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until 1950 that his Three Laws of Robotics became widely known. These laws, first introduced in his short story “Runaround,” set the foundation for how science fiction would handle the complex relationship between humans and artificial intelligence.

Asimov's approach was both philosophical and practical, addressing the potential for robots to become both helpers and threats. His writing foreshadowed many of the ethical concerns we grapple with today, particularly regarding automation, artificial intelligence, and the impact of machines on the workforce. Asimov's robots weren’t merely tools; they were characters that reflected humanity's hopes and fears about its technological creations.

Virtual Reality

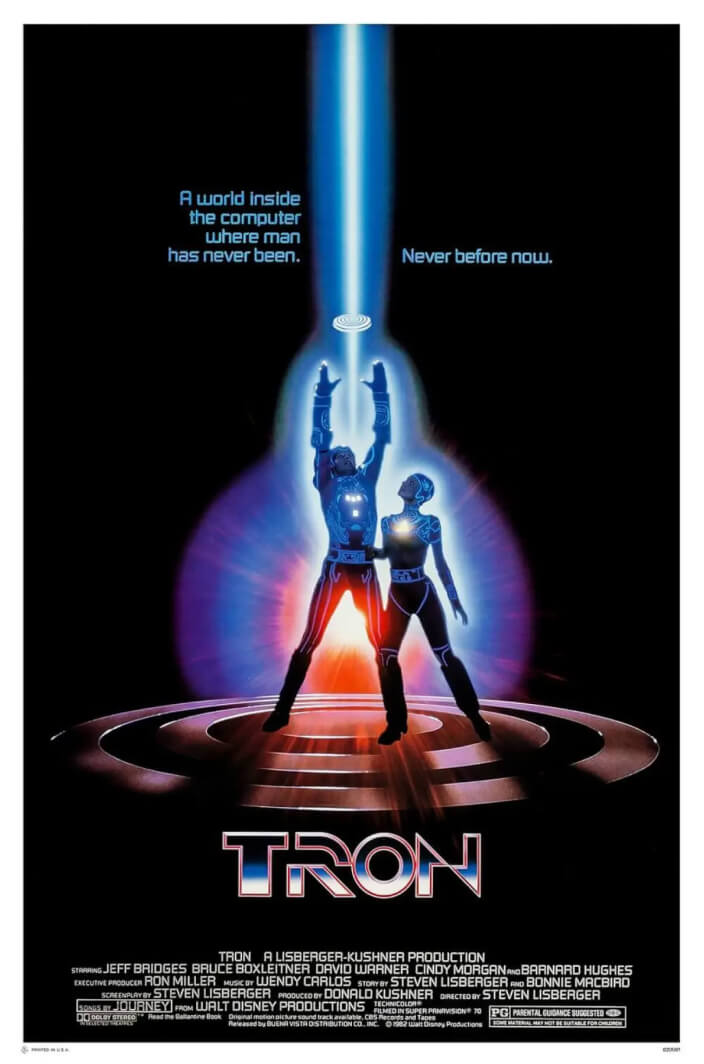

While the concept of virtual reality might seem like a recent development, it traces its roots to mid-20th-century literature. Writers like Laurence Manning and Stanislaw Lem laid the groundwork for virtual worlds in their stories, speculating on the boundaries between the real and the simulated.

In the 1980s, these ideas became clearer with the release of “Tron” (1982) and William Gibson’s “Neuromancer” (1984). Gibson, in particular, introduced the world to the idea of cyberspace—a virtual realm where individuals could interact with computer networks as if they were physical spaces. His work became a cornerstone of the cyberpunk genre, a reflection of society’s growing frustration with technology and its increasing dominance over daily life.

Irish-born British scientist and philosopher John Desmond Bernal introduced the term “science-technological revolution” in his 1957 work Science in History. Bernal highlighted the distinct phases of scientific development. The first revolution was the birth of the scientific method, the second saw science applied in a practical way. Тhe third, occurring in the XX century, marked the influence of science on production, the economy, and society.

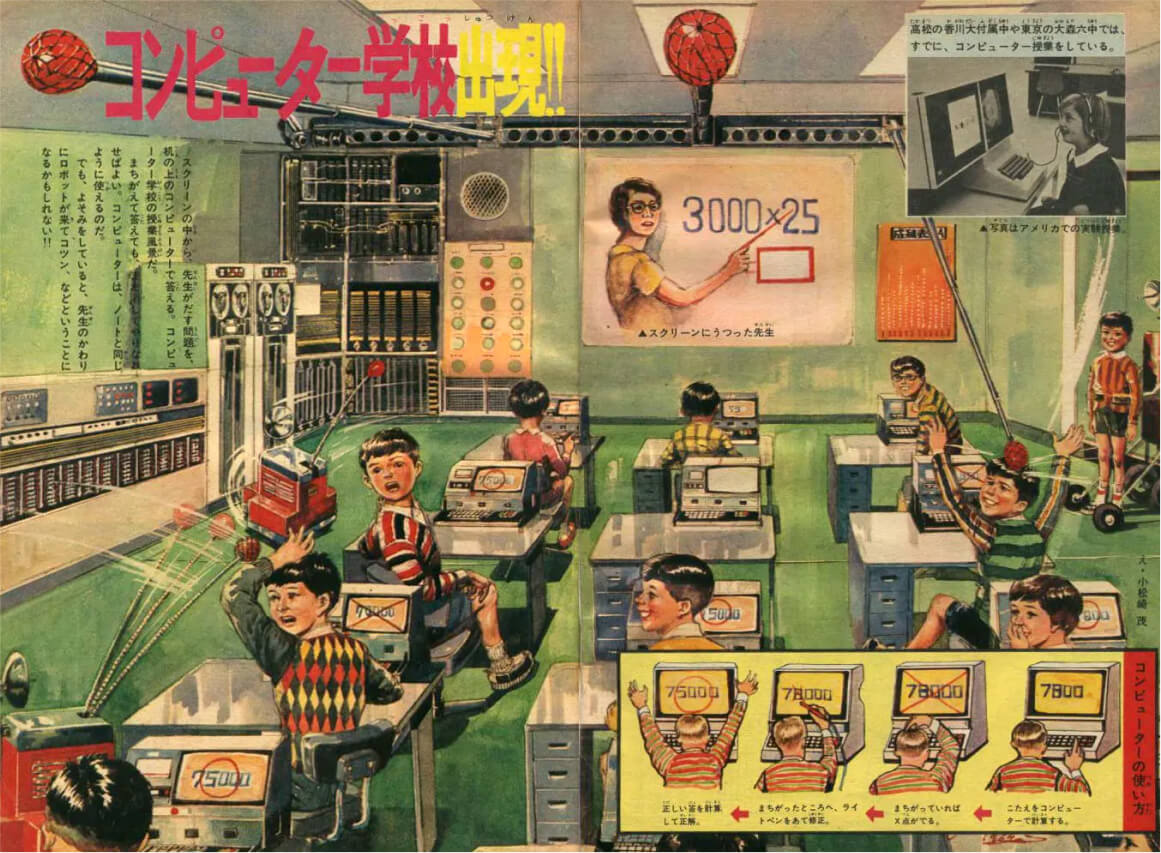

In 1969, Japan’s Shohen Sunday magazine illustrated a utopian future where robots and computers not only teach students but also discipline them when necessary. Source

This Marxist view of science's role in society was also popular among Soviet thinkers like Alexei Kosygin, who embraced the concept of a "science-technological revolution" in political discourse. However, the Soviet Union’s highly centralised, bureaucratic system hindered the integration of scientific and technological innovations into the economy.

In contrast, Western nations harnessed technological advancements to improve living standards, which prepared their citizens for the transition to the new technological era.

In the early 1950s, most industrialised countries were engaged in some form of computing development, but these efforts were largely uncoordinated. Occasionally, a laboratory would publish a book or article that gained wide circulation, but overall, the connections between projects were informal and sporadic even within the West.

Isaac Auerbach, a computer scientist who contributed to early computing at Burroughs and Sperry Univac, envisioned a more systematic approach to connect global computing efforts. He aimed to elevate the universality of computation to an international platform and sought support from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

In 1959, the first International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP) Congress was held in Paris, and the organization still active today. Around this time, English became the lingua franca for computing and other scientific disciplines, a trend that has shaped many aspects of modern civilization.

The IBM System/360, introduced in 1964, marked a significant milestone in the standardisation of computer technology. It allowed compatibility between different models and facilitated the reuse of software, reducing the need for reinvention. This set the stage for later systems, including the IBM PC architecture, which further promoted unified standards in computing.

By the late 1980s, the curriculum for informatics and computer science in schools grappled with issues of compatibility, although the variability of systems had decreased compared to the early days of computing in the late 1940s and 1950s.

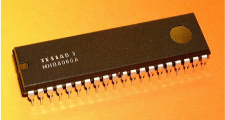

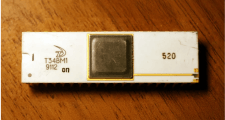

A Soviet clone of the Intel 8080, the core for many computing machines, including DIY projects. One of the fastest reverse engineering efforts in the USSR, it was put into mass production in 1977, only three years after the original i8080 was released.

A Czechoslovakian clone of the Intel 8080, produced between 1983 and 1989, was widely used in educational and home computers such as the PMI-80, PMD 85, and Didaktik Alfa.

Another clone of the Intel 8080, it was the only microprocessor produced in Poland during the mid-1980s. It served as the core for Elwro office computers and various videoterminals.

A Soviet clone of the Intel 8086 and the first 16-bit microprocessor replica was produced from 1985 onward. It became popular throughout the Eastern Bloc, enabling the creation of IBM PC-compatible machines such as the Iskra-1030 in Russia, the Mazovia in Poland, and the Poisk in Ukraine.

A Hungarian clone of i8080 produced by the Tungsram electronics factory in the suburbs of Budapest in the 1980s.

A Bulgarian clone of the MOS 6502, developed in the mid-1980s, that became the heart of Pravetz 8computers. The 6502 was rarely cloned in the Eastern Bloc, as the original was imported directly to the USSR.

An East German clone of the Zilog Z80, released in 1986, it became a crucial element in the cloning and design of DIY computers in Socialist countries during the second half of the 1980s.

A Romanian clone of the Zilog Z80 microprocessor, produced in the latter half of the 1980s, served as the foundation for DIY and clone computers like the Cobra and Felix.

Another clone of Z80, produced in the USSR in the late 1980s, was exported to Czechoslovakia for integration into the local Didaktik computer. It also became legendary as the foundation for DIY clones of ZX Spectrum across the former Soviet Union.

Notably, the East German Robotron computer company achieved significant success in cloning Zilog Z80 microprocessors. The resources of its Kombinat Mikroelektronik Erfurt started in the late 1970s were initially focused on the production of U808 and U880 clones.

Robotron delegates pull the carts with PC1715 computers based on the U880D microprocessors. Parade dedicated to the 750th anniversary of Berlin, July 1987. Source

These microprocessors were incorporated in K1510 and K1520 microcomputers widely adopted around the GDR. Later, they became essential for cloning ZX Spectrums.

The term "informatics" is usually traced back to the French "informatique," which combines "information" and "automatique" (automatic). It has been used since the 1960s to describe the processing of information through automated means, primarily with computers, and quickly spread across Europe.

Starting from the late 1960s, the electronic industry in socialist countries primarily focused on cloning Western examples, emphasising mass production over original solutions. By the mid-1980s, personal computers had spread across both the First and Second Worlds, though the Eastern Bloc lagged behind its Western counterpart.

Mass computerization in socialist countries was partly fueled by a local DIY movement, with thousands of enthusiasts building their own devices. Unlike computers, the components became relatively accessible—together with informatics lessons in schools, it further paved the way for broader access to technology in Eastern and Central Europe.

Here are some of the most significant computers of the increasingly connected world of the 1980s, which, while familiar to kids in the global West, also inspired handy engineers in the global East.

Origin: USA

Year: 1977

Chip: Zilog Z80

A desktop microcomputer launched by the Tandy Сorporation to be sold in its huge network of Radio Shack consumer electronics stores. It was the best-selling PC until 1982, beating Apple early offerings. Tandy Radio Shack cost only $399 in its basic version, which made it much more attractive among all competitors.

WOW! In the first year after the launch of TRS-80, over 250,000 people were on the waiting list to buy it.

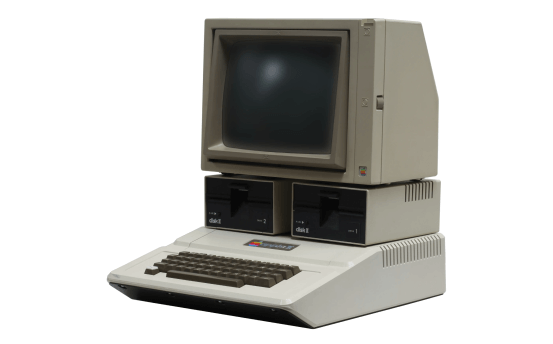

Origin: USA

Year: 1977

Chip: MOS Technology 6502

A pioneering microcomputer designed by Steve Wozniak, the Apple II was one of the first highly successful personal computers. Known for its colour graphics, expandability, and ease of use, it helped Apple gain a foothold in the emerging PC market. Priced at $1,298, it was still attractive due to its advanced features and quality.

WOW! The Apple II remained in production for nearly 16 years, selling millions of units and establishing Apple as a major player in the industry.

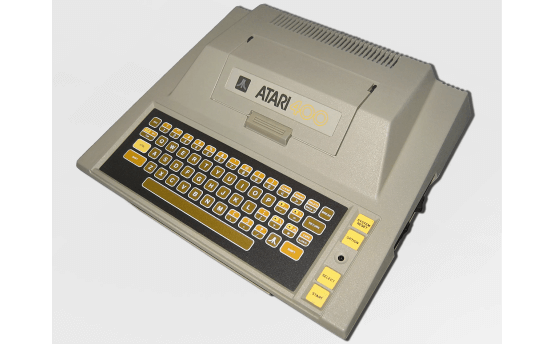

Origin: USA

Year: 1979

Chip: MOS Technology 6502

The Atari 400 was designed as a family-friendly device, part of the company’s effort to transition from arcade games to home computers. It featured a spill-resistant membrane keyboard, though it wasn’t ideal for extensive typing.

WOW! The Atari 400 offered impressive graphics and sound for the time and was considered one of the best machines for gaming and educational software.

Origin: USA

Year: 1981

Chip: Intel 8088

The IBM PC revolutionised the personal computing industry and set a new standard for desktop computers. It featured an open architecture, allowing third-party developers to create compatible software and hardware, which accelerated its adoption. Priced at $1,565, it was targeted at both business and home users, making it one of the most influential computers in history.

WOW! The IBM PC’s success led to the rise of “IBM-compatible” computers, dominating the market and shaping the future of personal computing.

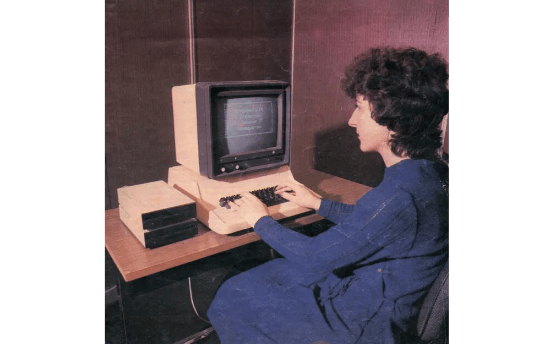

Origin: Bulgaria

Year: 1982

Chip: MOS Technology 6502

The Pravets-82 based on the Apple II architecture was the first Bulgarian personal computer produced on a large scale. It was primarily used in schools, universities, and research institutes across Eastern Europe with its production rising from 500 units in 1983 to 60,000 at the end of the decade. Priced significantly lower than Western counterparts, it played a key role in the computer education of an entire generation in the region.

WOW! The Pravets-82 was a point of national pride and laid the foundation for the development of Bulgaria’s computer industry in the 1980s.

Origin: USA

Year: 1982

Chip: MOS Technology 6510

The Commodore 64, often referred to as the C64, became one of the best-selling home computers of all time. Known for its advanced graphics and sound capabilities, it quickly gained popularity for gaming, programming, and educational use. Priced at $595 and available at general retailers, it was affordable for many households, contributing to its long-lasting success.

WOW! The Commodore 64 sold over 17 million units worldwide, making it an icon of 1980s home computing and gaming culture still popular among hobbyists.

Origin: UK

Year: 1982

Chip: MOS Technology 6502

The BBC Micro was developed by the Cambridge-based Acorn Computers for the BBC's Computer Literacy Project. Known for its reliability and expandability, it became the standard educational computer in British schools during the 1980s. Priced at £235, it was more expensive than some competitors but was praised for its durability and performance.

WOW! The BBC Micro played a crucial role in teaching a generation of students to code, inspiring many future tech leaders, and restyled versions can still be found on marketplaces today.

Origin: UK

Year: 1982

Chip: Zilog Z80A

The ZX Spectrum, developed by Sinclair Research, became one of the most popular home computers of the 1980s. Known for its distinctive rubber keyboard and vibrant color graphics, it significantly influenced the home computing and gaming markets. Priced at £125, it democratized computing and inspired a generation of programmers and game developers.

WOW! The ZX Spectrum’s success led to a vibrant software ecosystem, a devoted fan base, and millions of unofficial clones sold worldwide, making it an iconic piece of computing history and a cornerstone of early home computing culture.

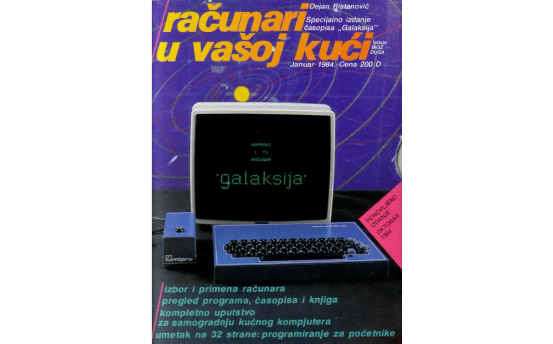

Origin: Yugoslavia

Year: 1983

Chip: Zilog Z80

The Galaksija was a do-it-yourself computer kit featured in the Yugoslav magazine “Računari” u vašoj kući (Computers at Your Home). It was a low-cost alternative to commercial computers, allowing enthusiasts to build their own machines from components. The Galaksija played a key role in spreading computer literacy in the region and became a symbol of the early DIY computer movement in Yugoslavia.

WOW! The engineer Voja Antonić, who developed the Galaksija schematics, began his work by researching the American TRS-80. To bypass the German import restrictions, the TRS-80 was sent to him in two separate pieces.

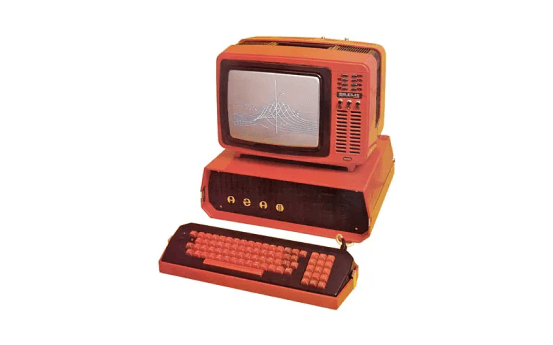

Origin: USSR

Year: 1983

Chip: MOS Technology 6502

The Agat was a Soviet home computer designed to be accessible for educational and personal use. Its relatively simple architecture made it widely used in schools and for programming practice across the USSR. Until 1985, the devices were assembled at the Scientific Research Institute of Computer Complexes in Moscow as no manufacturing facilities were willing to produce them.

WOW! A test unit of the Agat computer, assembled in a distinctive red case, was used for marketing presentations and even appeared on the cover of Byte magazine.

Origin: East Germany

Year: 1983

Chip: U880

The Robotron PC 1715 was an 8-bit computer developed for office and educational use but could also be adapted for laboratory and technological applications. It stands out as one of the few personal computers produced by the East German industry.

WOW! Nearly half of the Robotron PC 1715 units manufactured in the late 1980s were exported to the USSR, totaling around 50,000 units.

Origin: USA

Year: 1984

Chip: Motorola 68000

The Apple Macintosh 128K was developed nearly simultaneously with the Apple Lisa, Apple's first computer to use a graphical user interface (GUI). While the Lisa was groundbreaking, the Macintosh proved to be more stable and far more marketable, eventually becoming an iconic product.

WOW! The Apple Macintosh 128K’s launch was accompanied by an iconic Super Bowl ad directed by Ridley Scott, inspired by George Orwell’s 1984. This ad remaining a landmark in advertising history helped establish the Macintosh as a cultural phenomenon.

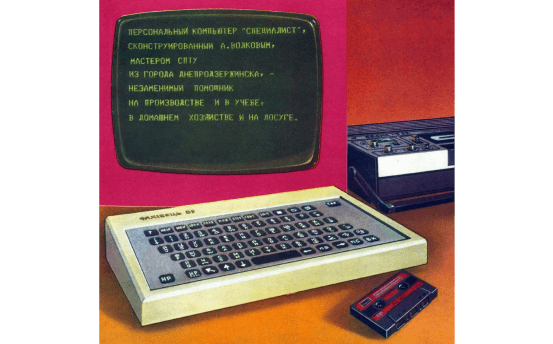

Origin: Ukraine (USSR)

Year: 1985

Chip: KR580VM80A

The Fahivets-85 was a Ukrainian 8-bit computer developed by teacher and radio enthusiast Anatoly Volkov to equip a school lab. Designed as an affordable option using relatively cheap components, it even offered black-and-white graphics. Though not as widely known as its Western counterparts, it played a key role in the early spread of computer literacy in Ukraine and other parts of the USSR.

WOW! The Fahivets-85 was known for its robustness in office environments, and in 1987, its schematics were published in a magazine, making it accessible to DIY enthusiasts.

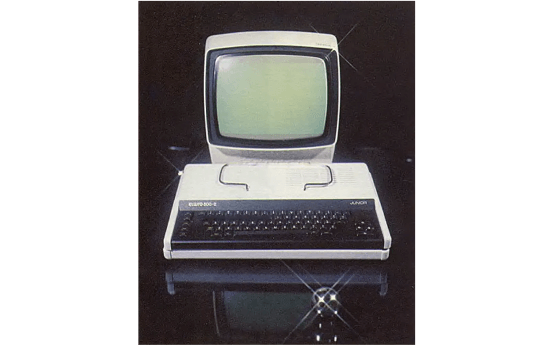

Origin: Poland

Year: 1986

Chip: U880

The Elwro 800 Junior was a Polish 8-bit computer designed primarily for educational purposes. It became a staple in Polish schools, providing students with their first experience in programming and computing. Compatible with the ZX Spectrum, it allowed access to a wide range of software.

WOW! The paper holder on top of the main computer unit was originally designed for the Elwirka electro-piano, which was assembled at the same Elwro plan using the same case.

Origin: Romania

Year: 1986

Chip: Zilog Z80

The Cobra began as a grassroots project in 1984, with its creators relying solely on a German-language Spectrum book as their guide. Despite limited resources, the Cobra became a success, filling a gap in Romania's technology market. Orders soon came in from state factories, and research institutes, establishing the model as a valuable tool in industrial settings.

WOW! In the dormitories of Bucharest's Polytechnical Institute, students assembled Cobra computers using black-market boards and circuits, earning money and helping to make computer technology more accessible during a time of scarcity.

Origin: USSR

Year: 1986

Chip: KR580VM80A

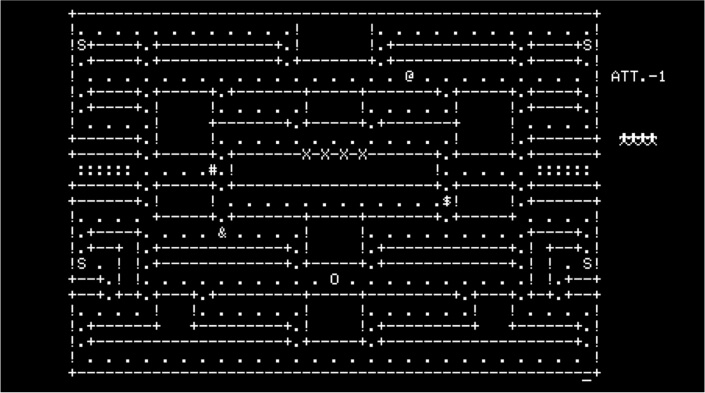

The Radio-86RK was a do-it-yourself computer kit that gained popularity through the Soviet magazine Radio in 1986. The magazine published detailed instructions, giving radio enthusiasts the chance to assemble their own computer at home. Though it lacked true graphics capabilities, clever use of symbol-based pseudo-graphics allowed users to design simple games and applications.

WOW! Although the Radio-86RK used only 29 chips, acquiring them was a challenge. Many resourceful hobbyists turned to smugglers who stole chips from factories.

Origin: USA

Year: 1987

Chip: Motorola 68000

The Amiga 500 was a groundbreaking home computer that brought multitasking capabilities, vibrant graphics, and advanced sound to an affordable price point. It quickly became the most popular model in Commodore’s lineup, known for its impressive multimedia features that made it a favourite among gamers and creative professionals.

WOW! The Amiga 500’s advanced sibling, the Amiga 1000, gained additional fame when artist Andy Warhol used it to create a live painting of Debbie Harry, the lead singer of Blondie.

Today, the word “informatics” is primarily used in an academic context to emphasise the systematic study of information processes and systems. However, "informatics" and "computer science" are closely related. In the 1980s, the two terms were mainly distinguished by geography, with "computer science" reflecting the influence of the USA.

The term “computer literacy” was originally coined by Andrew Molnar in his article “The Next Great Crisis in American Education: Computer Literacy,” published in 1978. In January 1979, it appeared in a New York Times article headlined “Johnny’s New Learning Challenge: Computer Literacy,” thus introducing it to a wider audience.

Various UNESCO boards frequently discussed computer awareness and its introduction into educational processes. The International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP) held its own conferences on the subject, which became annual in the 1980s. Before that, IFIP and UNESCO organised events that were devoted explicitly to education every five years.

In 1981, Andrey Yershov, a Soviet academician and a major popularizer of informatics in schools, gave his famous speech at the third global educational IFIP and UNESCO conference in Lausanne. His presentation, titled “Programming, the Second Literacy,” became an important statement for its time.

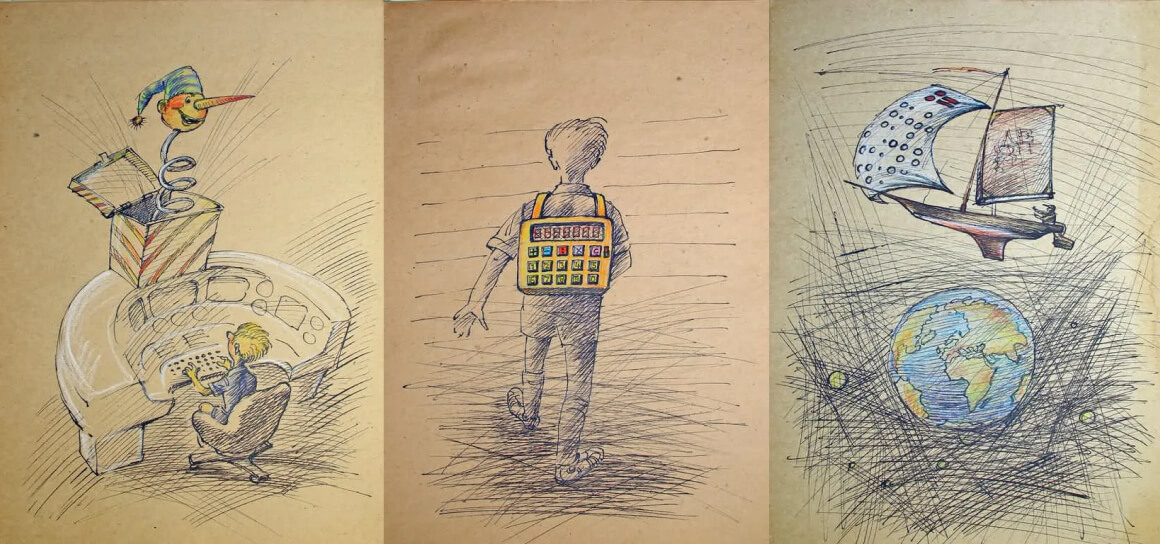

Three out of the 32 illustrations prepared by the artist Mikhail Zlatkovsky as supporting materials for the academician Yershov’s speech in Lausanne. (Source: Andrey Yershov’s archive)

“The computer will not only be a technical tool of the educational process, but it will also be an essential part of it. The new intellectual background and operating environment will be formed organically and naturally through the child's development at school and home. This will accelerate the child's intellectual maturation, increase their activity, and better prepare them for professional activity, including the second industrial revolution caused by the emergence of computers and new forms of automation.”

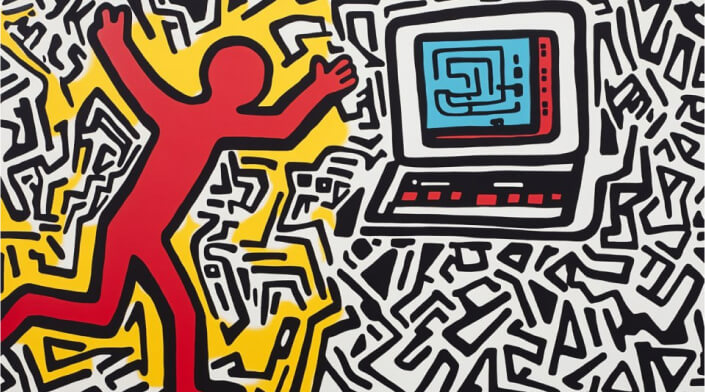

By the 1980s, at the peak of the Cold War, primary programming skills for high school graduates were seen as critical for national defence and industrial competition. In the USA, schools adopted the Logo and BASIC languages and included them in their curriculum.

The word “literacy” became common in the rhetoric surrounding mass computer science education in the 1980s. Literacy is often considered a primary goal of elementary education, and since the nineteenth-century mass education movement, children have frequently been the focus of literacy measurement. And governments of various states made a stake on enlightening their population to succeed in the economic and industrial competition.

In the 1980s, computer technologies introduced a wave of terms that quickly became integral to everyday conversation. Words and expressions like “mouse,” “file,” or “hard reset” entered common usage and redefined the way people interacted with technology and information.

As people became familiar with computers at school, work, or home, they spread the word to change language and communication. We have categorised these new terms into various topics, offering a look at the core components of computer systems, the evolution of graphical user interfaces, data manipulation tools, communication methods, symbolic representation, programming languages, and the cultural phenomena that emerged from this technological boom.

By outlining the origins and significance of these concepts, we highlight how they became the building blocks for modern digital literacy and an essential part of our global lexicon.

The microprocessor, a miniature circuit introduced in the early 1970s, became the core of every computer, whether a powerful business machine or a home device mainly used for recreation. The term 'CPU' (central processing unit) is a remnant from the days when this unit was a physically separate component, often the size of a refrigerator.

A computer is a complex system composed of various microdevices that must work together. The process begins with loading a bootstrap program, commonly known as 'booting.' If an error occurs, rebooting can reset the system.

System operation required a full control of the computer hardware. The Basic Input/Output System (BIOS), managing low-level programming and hardware interaction, was typically stored on Read-Only Memory (ROM) devices.

The primary hard drive, which was a solid alternative to floppy disks, punch cards, or magnetic tape, was usually designated as 'C:' (though this could vary), while floppy disk drives were labelled 'A:' and 'B:' and used for booting and loading software. Early home computers often lacked floppy drives and instead relied on cassette tapes with audio-encoded data.

The breakthrough in human-machine communication occurred in the late 1970s when engineers at Xerox developed a system for working with information through graphical representation. It became known as the Graphical User Interface (GUI). This innovation allowed people without deep technical knowledge to interact with computers.

To reduce costs, home computers were often connected to TV sets instead of dedicated displays. When graphic controllers emerged, users could explore the visual capabilities of computers, first in black and white, and later in colour, by blending several colour dots within a single sprite to enhance graphical representation. This evolution brought us more engaging computer games.

Initially, all data manipulation was conducted in text mode using operators and addresses. CRT displays, originally developed for military use, later became a convenient tool for instantly monitoring data output, eliminating the need to wait for printed results. This new technology allowed users to modify and correct programs on the fly, leading to the development of dialogue mode, which provided instant responses from the machine to user inquiries.

The concept of a cursor — initially a stationary indicator of the current position, later evolving to move along the line—was introduced to enhance user interaction.

Research in human-machine interfaces during the 1960s demonstrated the superiority of graphical representation for data manipulation. This approach eliminated the need for lengthy command requests, enabling more efficient user workflows. To imply this operation mode, a new device called a ‘computer mouse’ —an XY controller that guides the cursor on the screen—was introduced in the late 1960s and became commonplace by the end of the 1980s.

Gamers were also provided with a specialised device, the joystick, borrowed from arcade machines. It combined an XY controller with several buttons to control the action.

Computer networks were developed more than 20 years before the advent of home computers. These early networks relied on bulky, slow, and expensive equipment. Later more affordable versions of modems were created, enabling the interconnection of computers with different architectures.

This advancement gave private users access to early public computer networks, allowing them to share information and software. By the late 1980s, modems were often equipped with a fax (facsimile) option, enabling computers to function as fax machines for receiving facsimile documents.

One of the earliest methods of data transfer, File Transfer Protocol (FTP), was developed in 1971 by Indian computer scientist Abhay Bhushan and is still in use today.

Before graphics became standard, displays were text-based and limited to a set of standard symbols known as ASCII. Despite these limitations, engineers discovered ways to create images, resulting in what we now call ‘pseudo-graphics’.

These images often resembled ASCII art with human silhouettes or landscapes drawn using punctuation marks, special symbols, and letters. The introduction of real graphics—first in black and white and later in colour—marked a significant leap forward. Pixel-based bitmap images paved the way for the high-resolution images we see today.

Coding and programming used to be niche fields occupied by computer scientists and highly skilled specialists dedicated to supporting these scientists’ research. However, the boom in automation and digitalization has transformed this landscape with computers now integral to nearly every aspect of human life.

Algorithms and programming codes have become standard elements of education in industrialised countries, and the terminology has entered common usage, often popularised by science fiction literature and media.

This shift claimed unique educational approaches to teaching algorithms to children in an engaging and understandable way. The BASIC language, developed in 1964, was a game-changer and remains a foundational tool for teaching programming. Similarly, the LOGO language, with its iconic turtle robot, has made the learning process more playful and accessible.

The Information Age, which began with the early computers of the late 1940s and became more prevalent from the 1970s onwards, has transformed how we handle data in business, industry, finance, politics, and entertainment. This era introduced a bunch of new terms into everyday language.

The term ‘file’ originally referred to a collection of data, derived from the Latin word meaning 'tied with a wire.' Over time, it evolved into a more complex concept involving multiple data sets managed by a file system and file manager on storage disks.

The development of disk operating systems (DOS), such as MS-DOS and Apple DOS in the early 1980s, allowed users to manage files through command-line interfaces. Text-based file managers like Norton Commander, introduced in the mid-1980s, provided a more user-friendly interface for monitoring and managing files on screen.

Today, common file types include media formats like JPEG and PNG, whereas in the 1980s and 1990s, the most sought-after type was the *.EXE file, used to launch executable programs.

Before computers became widespread, a subculture of advanced users emerged, pushing the limits of technology. These users didn't just consume software—they created, shared, and modified it. They formed unique subcultures, such as the ‘demoscene’. Its members left their audio or video ‘intros’ inside the cracked software they exchanged at their events.

This era also saw the rise of keygens to bypass copy protection and hackers looking for bugs, setting viruses, and exploiting system vulnerabilities. These activities gave birth to urban legends of all-powerful hacking communities, inspiring the cyberpunk genre, which blends futuristic technology with countercultural themes and shapes them in its unique aesthetics.

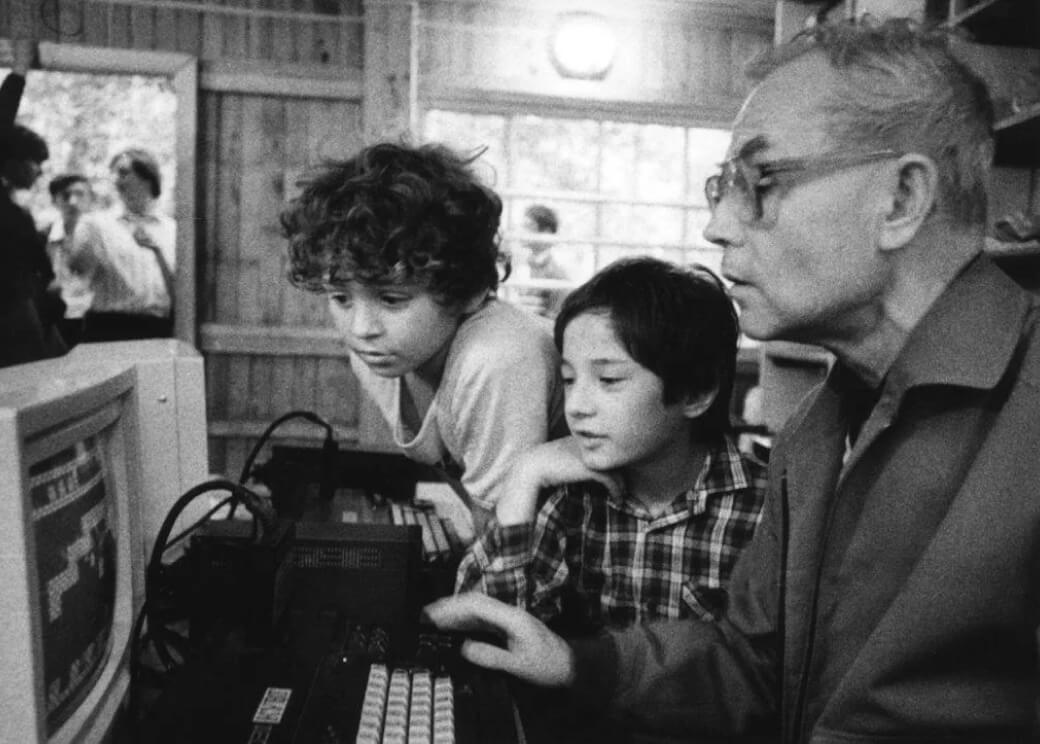

In the USSR, Academician Andrey Ershov successfully initiated the integration of practical computer skills into school curricula. The Soviet industry supplemented the process with various computing tools, including the Agat computer, a Soviet version of the Apple II, which became a common sight in classrooms. Additionally, the Soviet government promoted the use of the Rapira programming language, designed specifically for educational purposes.

Academician Andrey Ershov demonstrates a computer game to Young Programmers Summer Camp participants. (Source:Andrey Ershov’s archive)

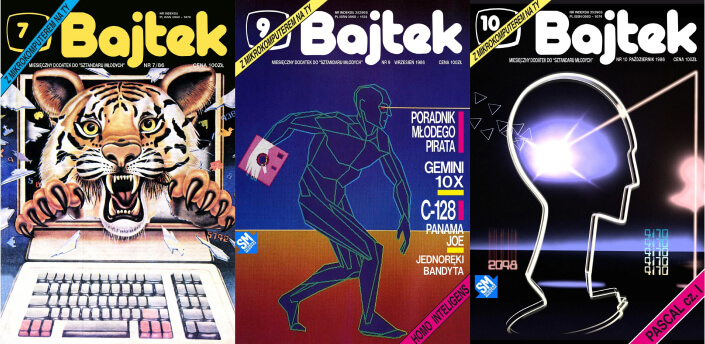

Media widely supported educational efforts across multiple countries. In the 1980s, the BBC even commissioned its own home computer BBC Micro for its Computer Literacy Project. New magazines related to informatics and programming appeared from Northern Europe to Latin America. For example, only in Poland there were 25 different titles by 1985 (see more in. However, most were scientific in nature and had limited circulation.

In the mid-1980s, many countries around the world launched special programs to integrate basic programming knowledge and computer skills into secondary school education. These are only a few examples to illustrate the scale of this global initiative.

The need for mass school education came into focus during the 19th-century Industrial Revolution. Workers with better basic training were more productive and efficient in adopting modern technology, despite the limited opportunities available to working-class children. Various industries demanded engineers, while armies and governmental offices sought educated staff to face modern challenges.

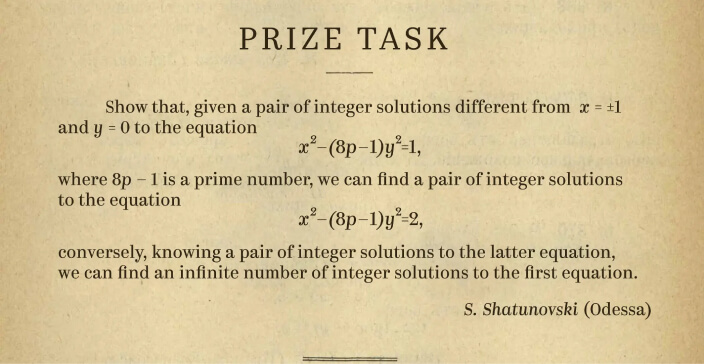

The Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires were among the first to apply competition to the knowledge gained in schools. The Russian Astronomical Society organised its first Olympiad for students in the 19th century. Between 1885 and 1917, the journal "Bulletin of Experimental Physics and Elementary Mathematics" published tasks for children, thus hosting the very first correspondence Olympiad.

In 1894, the Hungarian Mathematical and Physical Society launched the Eötvös Mathematics Competition, which is still held today under the name Eötvös-Kürschák. In the 1920s, Hungarian mathematician and physicist John von Neumann attempted to establish a similar contest in Germany. After World War II, another Hungarian mathematician, Gabor Szegő, working at Stanford University, was inspired by its framework to organize a competition in California.

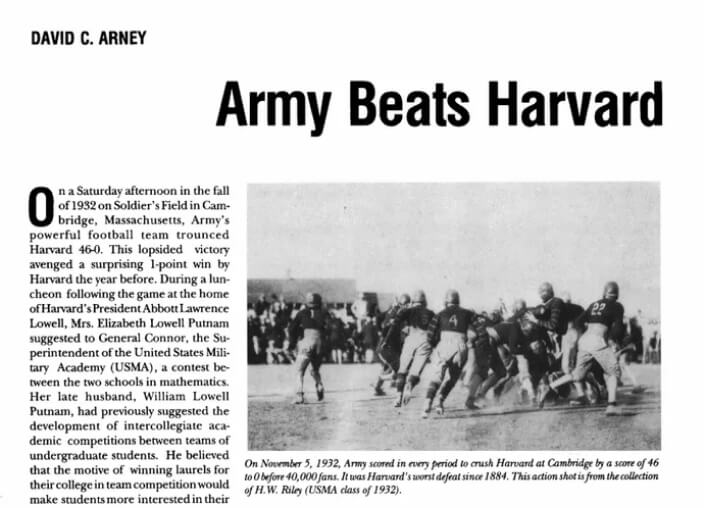

In 1933, two events marked the new stage in mathematics competitions history. In spring, cadets of the US Military Academy in West Point won a unique contest against Harvard students. In December, the first large competition was held in the USSR, i.e. in Tbilisi. The latter was followed by official Mathematical Olympiads in Leningrad (1934) and Moscow (1935).

In the 1950s, Eastern and Central European countries, operating under the general guidance of the USSR, began engaging in educational exchanges for students and schoolchildren meant to strengthen academic ties within the socialist bloc. Starting in 1959, this collaboration expanded to include international competitions in mathematics and science.

The first International Olympiad in Mathematics in Brasov, Romania.

The first Olympiad in Physics in Warsaw, Poland.

The first Olympiad in Chemistry in Prague, Czechoslovakia.

Originally started exclusively for the countries of the Eastern bloc, the International Mathematical Olympiad accepted participants from over the world. In 1979, IMO was for the the first time held in the West, i.e. London.

From its very start the International Olympiad in Informatics didn’t have any geographical limitations. The 1989 contest in Pravetz., Bulgaria, was followed by Minsk in 1990, Athens in 1991, Bonn in 1992, and Mendoza, Argentina, in 1993.

The earliest programming contest for college students, the ICPC, dates back to the 1970s, initially involving participants from the USA and, to a lesser extent, Canada. The competition began at Texas A&M University in 1970 and became truly global in 1989, attracting young programmers from different continents. The team from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), seen in the photo, won that contest using the Apple Macintosh 128K computer visible on the desk. February, 1989 Source

One of the earliest competitions in the emerging field of programming took place in West Germany in 1980. Known as the "Bundeswettbewerb Informatik" (Federal Contest in Informatics; BWINF), it became an annual event starting in 1985.

Victor Bardadym,

Ukraine IOI team leader in 1990s:

“In the mid-1980s, the Institute of Cybernetics in Kyiv equipped a training laboratory with 8-bit Yamaha MSX KUWT computers, which were also installed in the nearby School No. 132. In 1986, this school hosted an innovative computer science Olympiad, organised in collaboration with the Institute of Cybernetics. The challenge of the final competition was to program a robot to navigate a labyrinth. It was at this event that future administrators of the '.UA' domain, Dmytro Kohmanyuk and Igor Sviridov, first met.”

In Bulgaria, national programming contests began in 1981, with the first nationwide Olympiad in Informatics held in May 1985. Bulgaria hosted its first international informatics competition, though not yet recognized as an Olympiad, in Sofia from May 17–19, 1987. This event, called the Open Competition on Programming, prefaced the second conference “Children in the Information Age.”

The Palace of Culture “Lyudmila Zhivkova,” which hosted the "Children in the Information Age" conference in May 1987, is shown in the photo by D. Dimov. Source

General computer education and competitive programming in Bulgaria were passionately promoted by Blagovest Sendov, a prominent scientist who led the National Academy of Sciences and represented the country at the International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP). The inaugural IOI President, Professor Peter Kenderov, was a distinguished mathematician with extensive experience in mathematical Olympiads.

Georgi Yordanov, Andrey Yershov, and Blagovest Sendov at a protocol meeting before the "Children in the Information Age" conference, May 16, 1987. From Andrey Yershov’s archive

Greetings to the IOI'89 participants from Evgenia Sendova, now an associate professor at the Institute of Mathematics and Informatics, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, who has been teaching courses for teachers on LOGO since 1985:

Welcome, welcome dear friends

representing many trends

coming to a competition

we hope it will become tradition.

Is it not a great idea

to gather all of you in here

to show that you are very clever

and you will become friends forever.

Higher, stronger, further wiser —

Friendship is the best adviser

At the IOI'89 in Pravetz, 16 teams comprising 46 students participated. An international jury selected a problem from a set of six prepared by the organising committee and evaluated the solutions presented by the teams. The competition lasted four hours.

Ivan Derzhanski,

coordinator at the IOI'89, now associate professor, co-chair of the board of the International Olympiad in Linguistics:

“It was my job to check and evaluate some of the students' work together with their team leaders and another coordinator, Emil Kelevedzhiev, who’s still my colleague at the Institute of Mathematics and Informatics. We judged teams from Bulgaria, the USSR, Poland and Cuba.”

Georgi Yordanov, Andrey Yershov, and Blagovest Sendov at a protocol meeting before the "Children in the Information Age" conference, May 16, 1987. From Andrey Yershov’s archive

Most of the competitors operated the local Apple II or IBM PC/ XT/AT/ compatible Pravetz computers provided by the hosts. Only one of the Soviet teams brought its own equipment. It was pretty remarkable for the time, as even in the 1990s, competition organisers often lacked sufficient devices, forcing some participants to solve algorithmic problems on paper.

![Derzhanski]()

Ivan Derzhanski,

coordinator at the IOI'89, now associate professor, co-chair of the board of the International Olympiad in Linguistics:

“I remember sitting at a table at lunch with the team leaders from Greece. In general, there was a lot of international communication—a good chance to practise different languages.”

The success of the first IOI transformed it into an annual event and promoted the idea of competitive programming worldwide, leading to the establishment of many national and regional contests in the 1990s. For example, Romania capitalised on its geographical position by hosting the Balkan and Central European Olympiads in Informatics in 1993 and 1994. The Baltic countries followed suit, founding their own competition in 1995, with the first BOI held in Tartu, Estonia.

The International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) has a rich heritage and a long-standing tradition of excellence in competitive programming. Since its inception in 1989, the IOI has offered a platform to showcase skills in algorithmic problem-solving.

While the Proggy-Buggy contest does not aspire to compete with the prestige of the IOI, we are proud to contribute to the diverse landscape of programming competitions. Proggy-Buggy offers a more relaxed and accessible experience.

Participants of the Proggy-Buggy contest in Lviv, Ukraine. Autumn 2023

By providing a fun and less intimidating environment, we hope to encourage more people to explore the joys of programming and perhaps even discover a new passion along the way.

You may test yourself solving the problem from the first IOI'89 in Pravetz and another one from the Proggy-Buggy’2023 programming contest by DataArt.

Created by

Editors

Alexander Andreev

Alexey Pomigalov

Design and layout

Ilya Korobov

Development

Maxim Pikulin

The DataArt IT Museum is a multi-channel historical project dedicated to exploring and promoting the IT engineering heritage in the regions where we operate, all within a global context. This initiative aligns with DataArt's core value of “People First,” as it celebrates the lives and contributions of pioneering computer engineers.

Our mission is to reconstruct the historical landscape surrounding significant engineering achievements, with a focus on aspects often overlooked in mainstream research. We spotlight little-known digital art, obscure subcultural electronic music, and the early experiences of local programmers — such as the computers they learned on in school and the games they played in computer clubs. Our team is passionate about 20th-century industrial design, old-school visuals, and early computer-age footage and memories.

We delve into the history of computer science and industry before globalization to uncover groundbreaking projects. Initially centered on Eastern and Central Europe, the museum has expanded as DataArt's presence has grown globally, uncovering stories of IT development in Latin America, India, and beyond. By weaving these local IT stories into a global narrative, we aim to tell the rich, diverse story of IT culture.